The I Ching is one of the oldest of the Chinese Classical Texts. Traditionally it is used as a tool for divination – the art of foretelling future events. It is essentially a means of obtaining spiritual guidance, inspirational insight and Universal wisdom. It can help with personal development or provide encouragement in finding authentic understanding and solutions to the questions or decisions that are of importance to you at any given time or situation.

The book acts not only as a spiritual compass but also offers a wealth of beautiful poetry and Chinese philosophy that stretches back 5000 years into the origins of ancient Chinese customs and values. Its wisdom has the potential to stimulate your sensitivity, creativity and resourcefulness, even whilst experiencing the most challenging and demanding emotional periods of your life.

In this regard the I Ching can also be helpful as a meditation support, providing comfort and guidance. The text and subsequent visualisations that flow from its words have the power to stimulate a deep-seated personal authentic vibration.

Luckily there’s no need to study or even understand Taoist philosophy to appreciate or benefit from the teachings of the I Ching. All that’s necessary is the sincerity and aptitude to explore the concept of aligning with natural and Universal laws and the energetic polarities of Yin and Yang.

Getting Started

The purpose of consulting the Oracle, as the I Ching is often called, is to gain mastery over one’s circumstances and thereby live a successful, spiritual life which may or may not include wealth and high position.

The 64 hexagrams represent archetypal behaviours to aspire to on a practical level. Since Nature, waxes and wanes, is in constant motion and is cyclical, whatever situation you find yourself in, has been and will come again. In depth study of the I Ching’s commentaries gives the student clues to be able to recognize any situation and guidelines on how to act in it. It is in this way, that it is said the I Ching can predict the future. It does not actually predict the future, it simply suggests that due to the cycles of nature, what has been will be again.

The first step in consulting the I Ching is to formulate a question and create a hexagram, typically though the process of throwing coins. There are several other ways to consult the I Ching – one traditional method uses grains of rice, another uses yarrow sticks (allegedly because Yarrow grows on the grave of Confucius), but the main method used in the West is throwing coins, usually Chinese, although any coins will do the job.

Creating Your Hexagram

After gathering your 3 coins, meditate on the question you are seeking guidance on. Some silent focus on your question will ensure that you have a clear connection when you are throwing your coins.

In throwing the coins the intention is to create a hexagram. Each hexagram is built up from a series of six lines, either broken or unbroken, which are considered to be a reflection of the energetic qualities of the situation at hand.

A straight line ‘_______’ represents Yang energy or young Yang, and a broken line ‘____ ____’ represents Yin energy or young Yin. There is also another energetic quality which reflects the fact that the Yin or Yang energy of any situation is dynamic and thus may be at the point of transformation, either from Yin to Yang or vice versa. These lines are called ‘moving’ or ‘changing’ lines and a can be Yin moving/changing (old Yin) or Yang moving/changing (old Yang).

If you use the coin method, every time you throw your three coins the outcome can be translated into an energetic line. By throwing the coins six times you then create the six lines that become the whole hexagram.

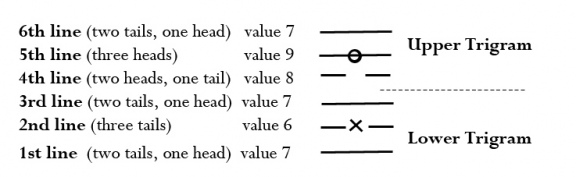

Once you have formulated your question you should select three coins which have an identifiable ‘head’ and ‘tail’ or two easily distinguishable sides that you can assign the following numerical values to:

Heads = 3

Tails = 2

By throwing the three coins their combined total value will fall between 6 and 9. For example, two heads and one tail would total 8, two tails and a head would total 7, three tails would total 6, etc.

These values can then be translated their energetic lines:

3 tails thrown = value of 6, represented as a Yin broken line which becomes a moving/changing line (old Yin), because the coins are identical:

2 tails and 1 head thrown = value of 7, represented as a Yang straight line (young Yang):

2 heads and 1 tail thrown = value of 8, represented as a Yin broken line (young Yin):

3 heads thrown = value of 9, represented as a Yang straight line, which becomes a moving/changing line (old Yang) because the coins are identical:

*Note that moving/changing lines within the hexagram are often represented with a ‘x’ or ‘o’ in the middle of the line to indicate that the lines are changing from Yin to Yang, or Yang to Yin, respectively.

The value and energetic line type of the first throw corresponds to the first or bottom line of the hexagram, the value and energetic line type of the second throw corresponds to the second from the bottom line, etc. Repeating this throwing action six times then builds the hexagram from the bottom up.

The bottom three lines of the hexagram are referred to as the lower trigram, and the top three lines are referred to as the upper trigram, together they make up the whole hexagram.

An example would be:

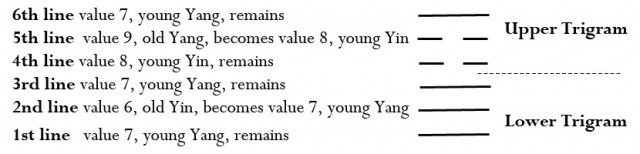

The Importance of Changing Lines

Each hexagram chapter is divided into two sections. The main opening text gives a broad overview of the message and should always be read. There’s also a series of six supplementary passages, each relating to one of the six lines of the hexagram. If you throw values of 6 or 9 and therefore have moving/changing lines within your hexagram you should also read the additional line passages that these correspond to for further guidance or insight.

With the hexagram example above, the second and fifth lines are moving/changing and so the line passages two and five should also be read alongside the main opening text.

Where moving/changing lines are present within your hexagram this can mean that the situation or question presented is in an extreme state of flux, unbalanced or due for immediate change and attention. In addition to reading the supplementary line passages within your primary hexagram chapter, the moving/changing lines can also be ‘allowed to change’: every old Yin (6) becomes a young Yang (7), and every old Yang (9) becomes a young Yin (8), and so a second extension (or relating) hexagram is created.

Your two hexagrams can then be read together (the main body text and relevant line passages of the primary hexagram and the main body text of the extension hexagram) to disclose the full meaning of the guidance being offered.

Using the example above, the following second extension hexagram would be created by allowing the moving/changing lines to transform:

The upper and lower trigrams of this extension hexagram are called ‘Ken’ and ‘Ch’ien’ respectively. Together they make up hexagram 26, called ‘Ta Ch’u, translated as ‘The Taming Power of The Great’.

This whole process can seem a little mechanical and cumbersome at first but don’t let it prevent your authentic consultation. The methodical and mindful nature of the practice is actually very important as it slows down your highly stimulated human-centred mind allowing you to access your more meditative, creative Tao mind, enabling a true reflection of the current situation or issue to manifest.

Looking up the Hexagram

After you are done throwing your coins and you have noted down your 6 lines (starting from the bottom up) you can move on to reading about the hexagram you received.

Just in case you don’t have a copy of the I Ching at home, below are some of the websites I use to look up hexagrams:

I Ching Calculator (This is a calculator which can be used instead of coins, but it’s accuracy isn’t unknown in comparison to throwing the coins yourself)

It is no accident that, of the early Jesuit scholars who were pioneers in making China’s culture known in Europe, those who concerned themselves with the Book of Changes were all later declared to be insane or heretic.

Indeed, to the Chinese themselves the study of the I Ching is not to be taken lightly. By an unwritten law, only those advanced in years regard themselves as ready to learn from it. Confucius is said to have been seventy years old when he first took up the Book of Changes. – Hellmut Wilhelm from Understanding the I Ching: The Wilhelm Lectures on the Book of Changes

> I Ching | Truth Theory

> Book of Changes | Compassionate Dragon